Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Conclusion

challenge

Discover why people act,

individually and jointly.

challenge

Discover why people act,

individually and jointly.

What is the relation between an instrumental action and the outcome (or outcomes) to which it is directed?

Answer 1

Intention ...

The outcome (or outcomes) to which an instrumental action is directed is that outcome (or outcomes) specified by the intention (or intentions) which caused it.

Distinction: goal-directed vs habitual processes

Potential Objection

Some instrumental actions may be consequences of habitual processes and not involve intention at all.

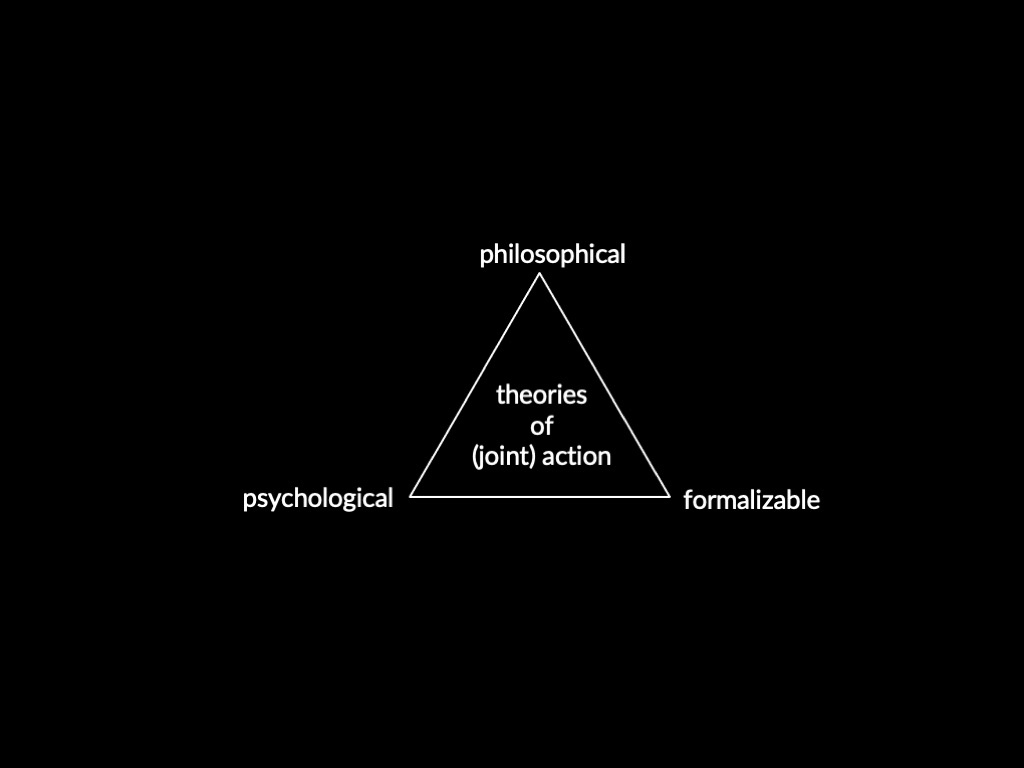

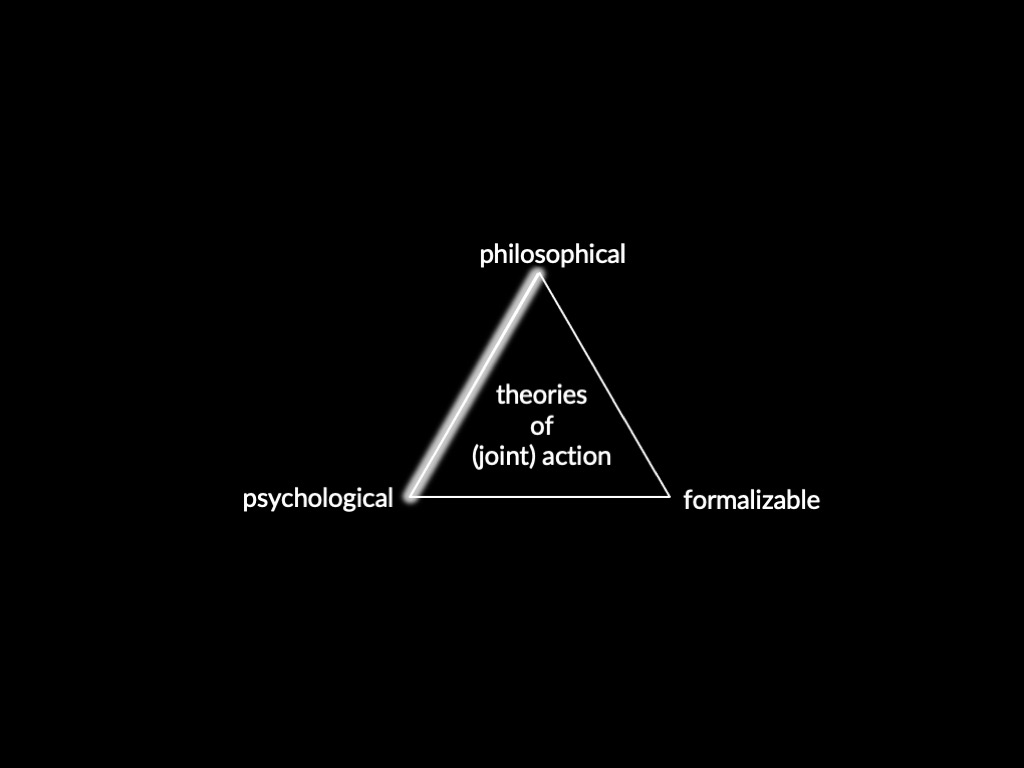

next step: relate it to philosophical theories of action

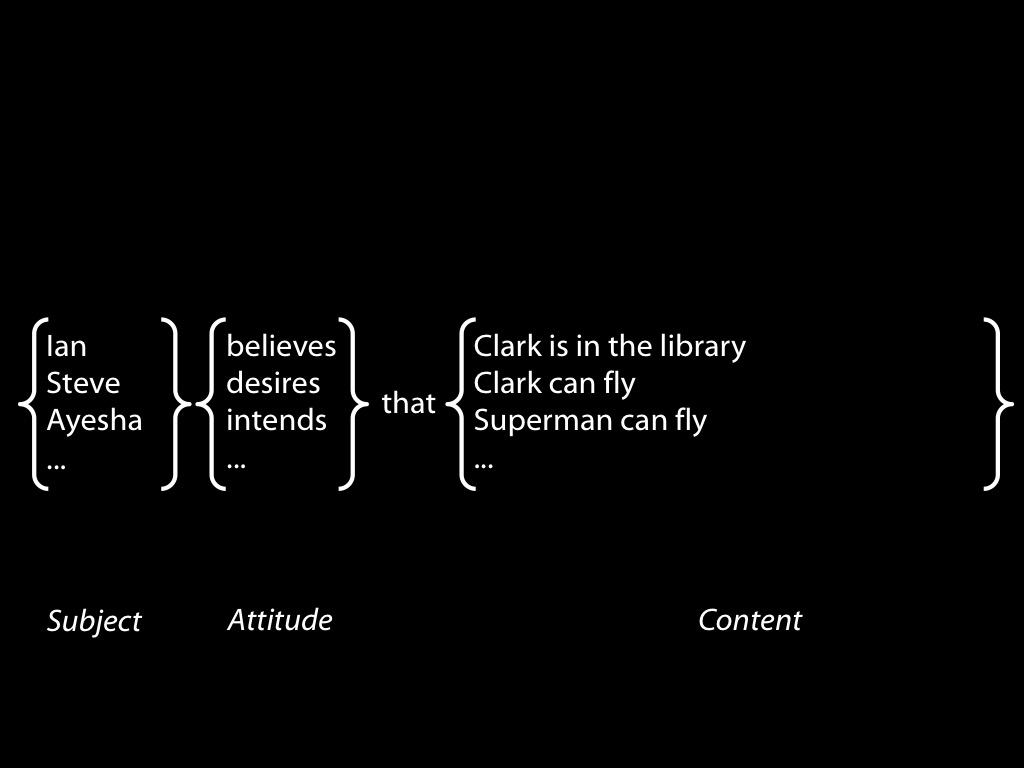

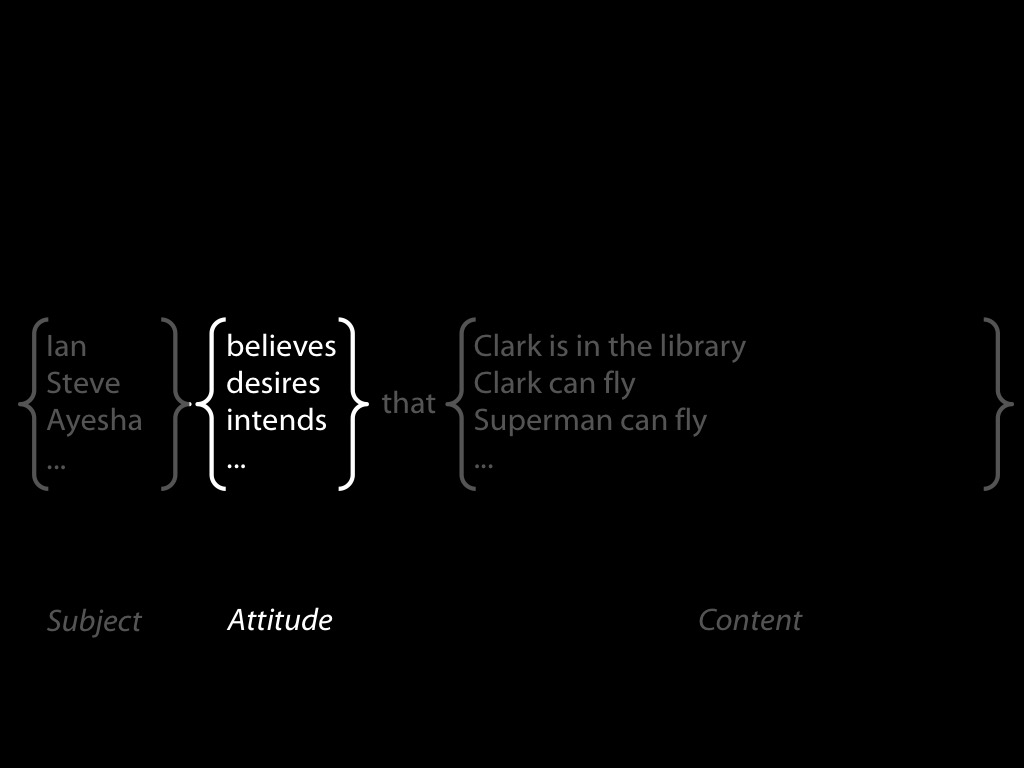

Question 1

What is the relation between an instrumental action and an outcome to which it is directed?

Standard Answer

The outcome to which an instrumental action is directed is that outcome specified by the intention which caused it.

Question 2

What distinguishes your actions from things that merely happen to you?

Standard Solution

Your actions are those events which stand in an appropriate causal relation to an intention of yours.

next step: evidence

appendix

habitual processes and desire/intention

outcomes:

press red → electric shock → pain experience

press green → chocolate flake → pleasure experience

stimulus–action associations:

buttons : press red [becomes weaker]

buttons : press green [becomes stronger]

During instrumental learning,

preferences can influence which experiences are pleasure and which pain,

and so which stimulus--action links are strengthened and weakened.

While acting,

habitual processes are entirely unaffected by your preferences.

habitual process

Action occurs in the presence of Stimulus.

Outcome follows action

Agent is rewarded

Stimulus-Action Link is strengthened due to reward

Given Stimulus, will Action occur? It depends on the strength of the Stimulus-Action Link.

‘goal-directed’ process

Action leads to Outcome.

Belief in Action-Outcome link is strengthened.

Agent has a Desire for the Outcome

Will Action occur? It depends on the Belief in the Action-Outcome Link and Agent’s Desire.

✔︎

habitual processes and desire/intention

appendix

what are representations?

‘an action is goal-directed if it is mediated by the interaction of a representation of the causal relationship between the action and outcome and a representation of the current incentive value, or utility, of the outcome in a way that rationalizes the action as instrumental for attaining the goal’ Dickinson (2016, p. 177).

‘As a first pass, representations are

‘‘mediating states of an intelligent system that carry information’’

(Markman and Dietrich 2001, p. 471).

They have two important features:

(1) they are physically realized, and so have causal powers;

(2) they are intentional, in other words, they have meaning or representational content.’

(Egan, 2014, p. 116)

‘There is significant controversy about what can legitimately count as a representation.’

(Egan, 2014, p. 117)

But why does Dickinson (and most scientists) talk about representation instead of sticking to belief, desire and the rest?

a further problem

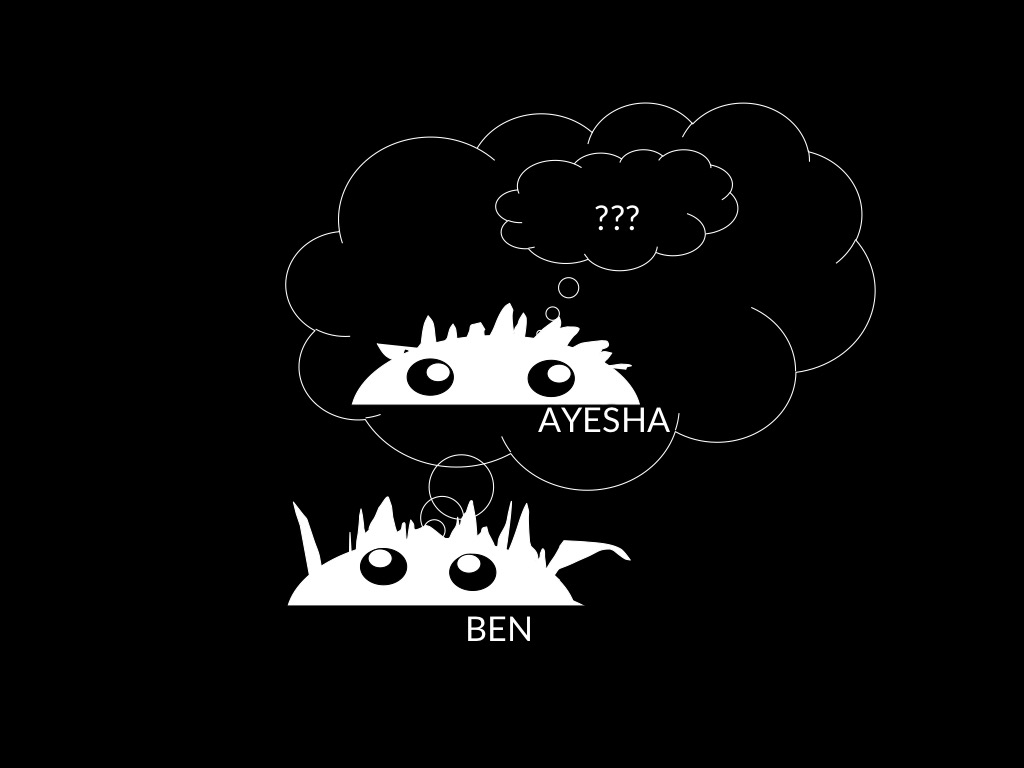

Functions of Ben’s model of minds and actions:

- ethical

- legal

- normative

- predictiveSecond, consider Ben’s concern with making predictions.

--- speed vs accuracy

Whenever you are making predictions about anything at all, you face a \textbf{trade-off between accuracy and speed}. Making more accurate predictions requires considering more information and integrating it in a more complex model of minds and actions. By contrast, making faster predictions requires narrowing the information you consider and using a less complex model of minds and actions. Since Ben often has to make predictions fast enough to actually coordinate his actions with Ayesha’s, and since making predictions consumes scarce cognitive resources, Ben is usually needs to trade accuracy for speed.So Ben’s model of minds and actions is not built for accuracy.

two problems

If we rely on beliefs and desires as paradigm cases of representation, ...

... we may thereby be rejecting some widely accepted claims about what representations are; and

... we may be relying on an unspecified notion that is not optimal for explanation.

habitual process

Action occurs in the presence of Stimulus.

Outcome follows action

Agent is rewarded

Stimulus-Action Link is strengthened due to reward

Given Stimulus, will Action occur? It depends on the strength of the Stimulus-Action Link.

‘goal-directed’ process

Action leads to Outcome.

Belief in Action-Outcome link is strengthened.

Agent has a Desire for the Outcome

Will Action occur? It depends on the Belief in the Action-Outcome Link and Agent’s Desire.

✔︎

what are representations?