Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Dual Process Theory Opposes Decision Theory?

habitual process

Action occurs in the presence of Stimulus.

Outcome follows action

Agent is rewarded

Stimulus-Action Link is strengthened due to reward

Given Stimulus, will Action occur? It depends on the strength of the Stimulus-Action Link.

‘goal-directed’ process

Action leads to Outcome.

Belief in Action-Outcome link is strengthened.

Agent has a Desire for the Outcome

Will Action occur? It depends on the Belief in the Action-Outcome Link and Agent’s Desire.

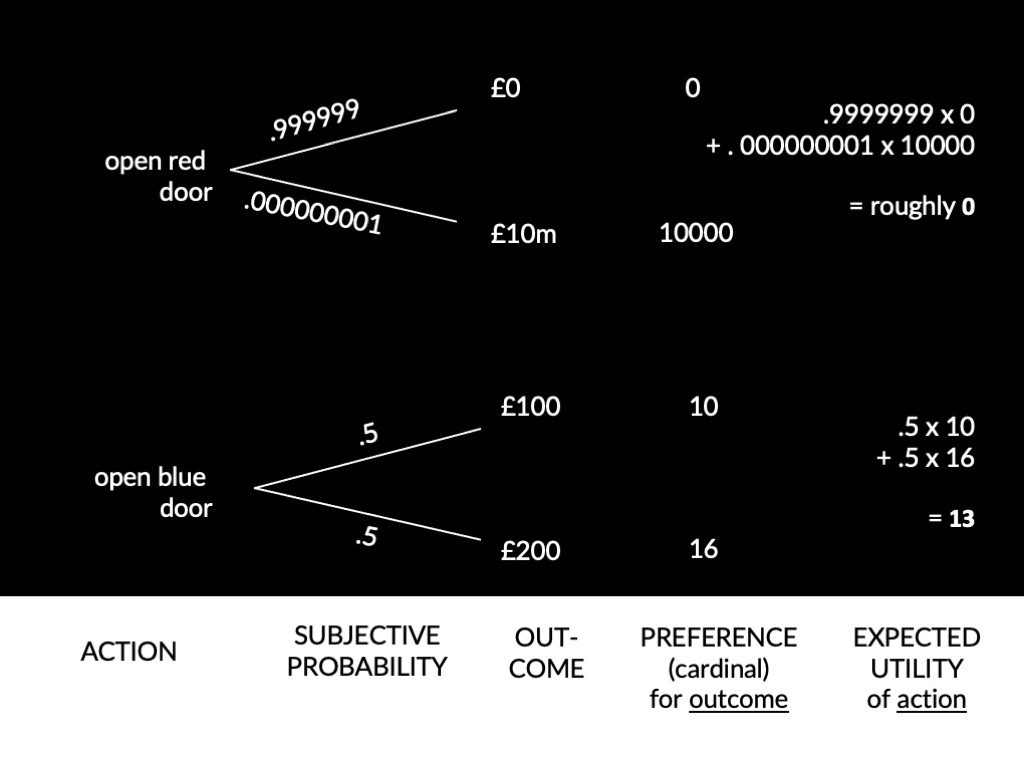

This book has ‘a philosophical end: elucidation of the notions of subjective probability and subjective desirability or utility’

(Jeffrey, 1983, p. xi)

key assumption:

Agents’ actions maximise their expected utilities.

This book has ‘a philosophical end: elucidation of the notions of subjective probability and subjective desirability or utility’

(Jeffrey, 1983, p. xi)

key assumption:

Agents’ actions maximise their expected utilities.

habitual process

Action occurs in the presence of Stimulus.

Outcome follows action

Agent is rewarded

Stimulus-Action Link is strengthened due to reward

Given Stimulus, will Action occur? It depends on the strength of the Stimulus-Action Link.

‘goal-directed’ process

Action leads to Outcome.

Belief in Action-Outcome link is strengthened.

Agent has a Desire for the Outcome

Will Action occur? It depends on the Belief in the Action-Outcome Link and Agent’s Desire.

This book has ‘a philosophical end: elucidation of the notions of subjective probability and subjective desirability or utility’

(Jeffrey, 1983, p. xi)

key assumption:

Agents’ actions maximise their expected utilities.

objection:

The assumption is unjustified given the dual-process theory.

inconsistent set

2. Decision theory provides an ‘elucidation of the notions of subjective probability and subjective desirability or utility’ (Jeffrey, 1983, p. xi).

3. The notions elucidated are those of belief and desire, which also feature in goal-directed processes.

4. Some, but not all, instrumental actions are dominated by habitual processes.

5. Habitual and goal-directed processes can pull in opposing directions.

response 1

‘the laws of decision theory (or any other theory of rationality) are not empirical generalisations about all agents. What they do is define what is meant ... by being rational’

(Davidson, 1987, p. 43)

but: elucidation was our goal

We are not objecting to decision theory.

We are objecting to a particular construal of it (as an elucidation).

construal 1: decision theory provides ‘mathematically complete principles which define “rational behavior”’

construal 2: decision theory provides an elucidation of belief and desire

response 2

It’s an approximation; the details don’t matter.

but: prediction vs elucidation

response 3

What maximises expected utility are not actions but goal-directed processes.

This book has ‘a philosophical end: elucidation of the notions of subjective probability and subjective desirability or utility’

(Jeffrey, 1983, p. xi)

key assumption:

Agents’ actions goal-directed processes maximise their expected utilities.

habitual process

Action occurs in the presence of Stimulus.

Outcome follows action

Agent is rewarded

Stimulus-Action Link is strengthened due to reward

Given Stimulus, will Action occur? It depends on the strength of the Stimulus-Action Link.

‘goal-directed’ process

Action leads to Outcome.

Belief in Action-Outcome link is strengthened.

Agent has a Desire for the Outcome

Will Action occur? It depends on the Belief in the Action-Outcome Link and Agent’s Desire.

Concerning the habitual process, what makes outcomes rewarding?

possibility 1:

the very system of preference that is involved in the goal-directed process

possibility 2:

not the system of preference that is involved in the goal-directed process

response 4

distinguish computational theory from implementation details

How to implement a utility maximizing agent?

option 1: search through potential actions, imagine consequences, evaluate how good they’d be

option 2: estimate best action from past rewards

option 3: combine 1 and 2

Having two processes

allows you to make complementary

speed--accuracy trade-offs:

habitual processes are fast but limited, whereas goal-directed processes are more flexible but slower

response 4

distinguish computational theory from implementation details

response 5

seek an alternative

‘Expected utility theory [...] has come under serious question [...]

There is now general agreement that the theory does not provide an adequate description of individual choice: a substantial body of evidence shows that decision makers systematically violate its basic tenets.

Many alternative models have been proposed’

(Tversky & Kahneman, 1992, p. 297)

But can the alternatives elucidate notions of belief and desire?

response 6

they do not exist

‘The problem with measuring risk preferences is not that measurement is difficult and inaccurate; it is that there are no risk preferences to measure—there is simply no answer to how, ‘deep down’, we wish to balance risk and reward.

And, while we’re at it, the same goes for the way people trade off present against future; how altruistic we are and to whom; how far we display prejudice on gender, race, and so on ...

there is no point wondering which way of asking the question [...] will tell us what people really want.

there can be no method...that can conceivably answer this question, not because our mental motives, desires and preferences are impenetrable, but because they don’t exist’

(Chater, 2018, pp. 123--4)

conclusion so far

This book has ‘a philosophical end: elucidation of the notions of subjective probability and subjective desirability or utility’

(Jeffrey, 1983, p. xi)

The dual-process theory of instrumental action, if true, complicates Jeffry’s claim that decision theory provides an elucidation of these notions.

so far ...

1. We understand what decision theory is

2. and how it can be used to provide us as researchers with a shared understanding of belief and desire.

3. This is necessary because not folk psychology, nor intuition nor philosophy provide a shared understanding.

4. If the dual-process theory of instrumental action is true, agents disobey axioms of decision theory, contradicting (2).

next

An independent argument with similar ingredients.