Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

The Problem of Action meets Habitual Processes

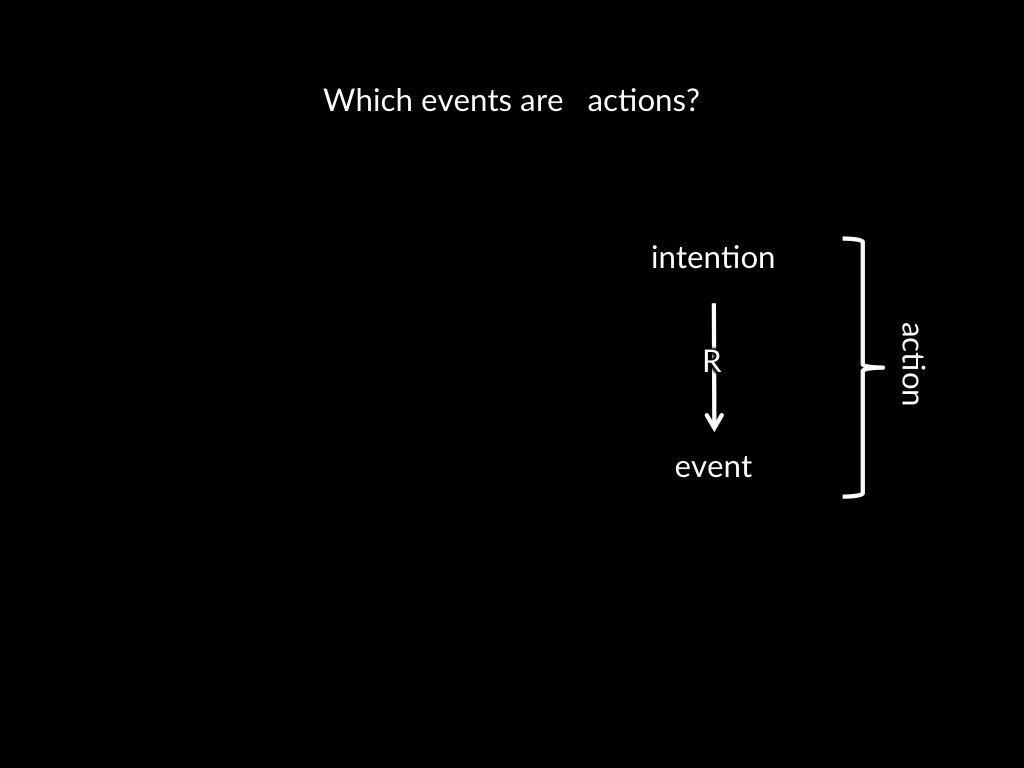

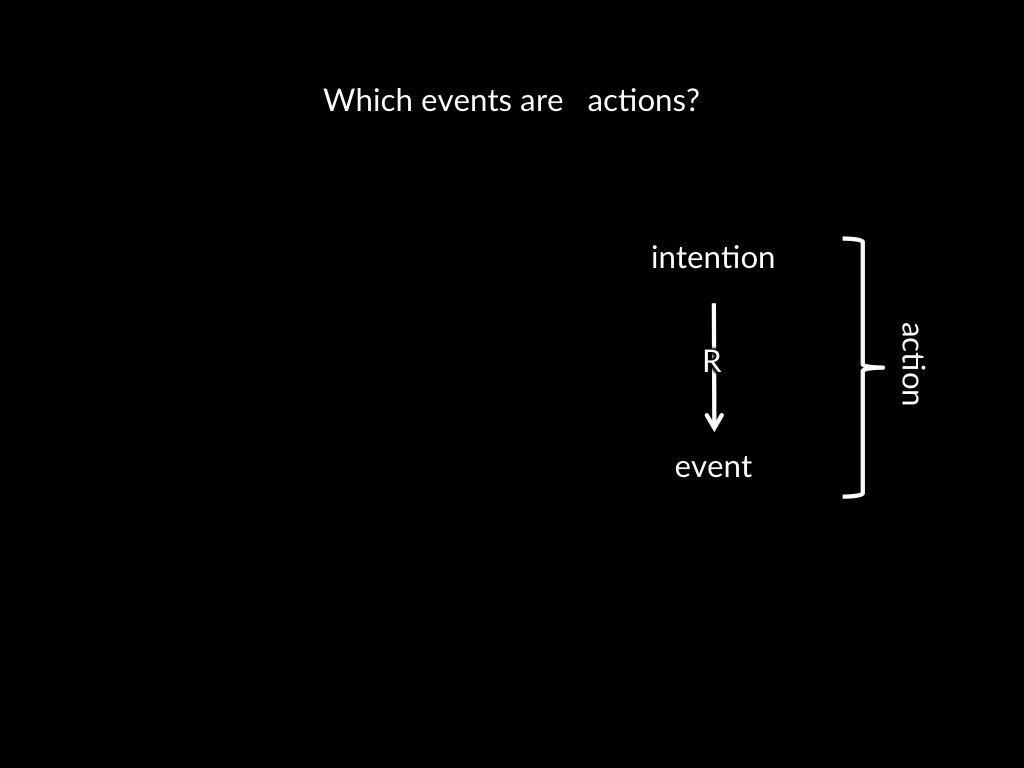

What distinguishes your actions from things that merely happen to you? (‘The Problem of Action’)

Standard Solution: actions are those events which stand in an appropriate causal relation to an intention.

‘deviant causal chains’ (Davidson, 1980, pp. 78--9)

Minimally, the action should not manifestly run counter to the intention;and neither should whether the action occurs be independent of what the agent intends.

Objection: some instrumental actions manifestly run counter to the agents’ intentions.

Why is this an objection?

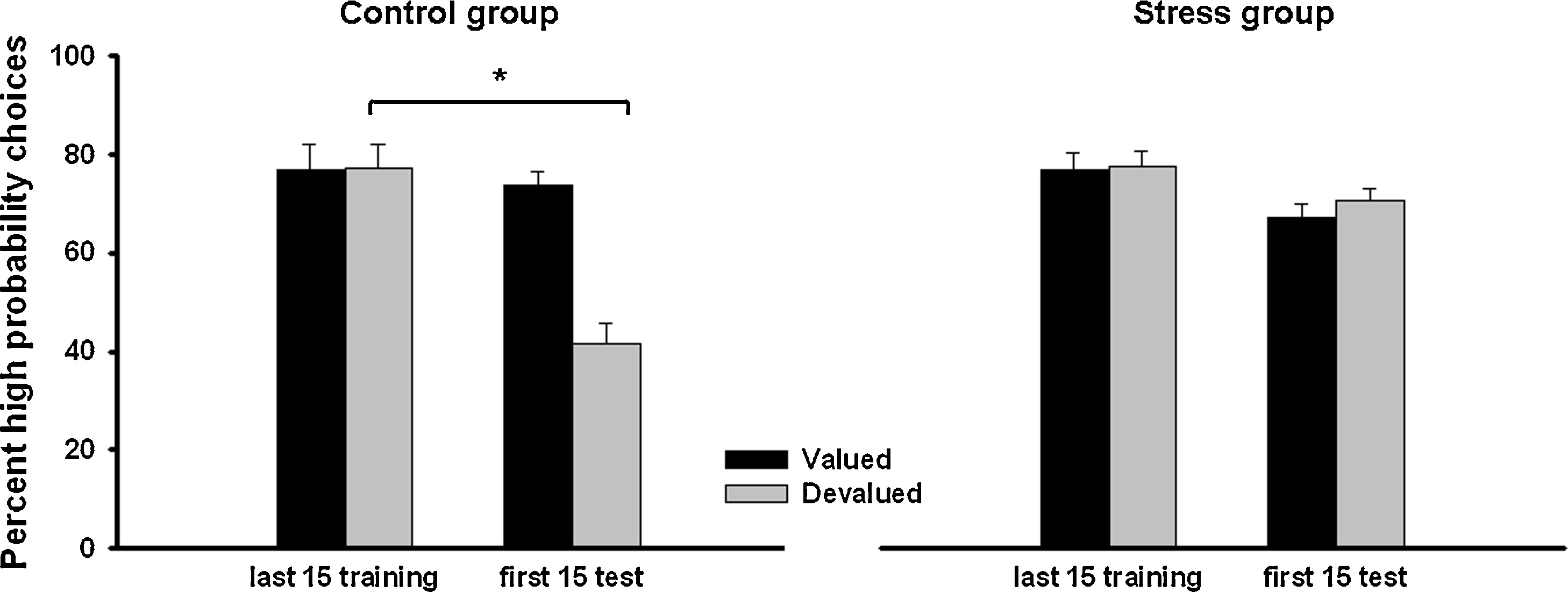

How do we know? From persistence following devaluation!

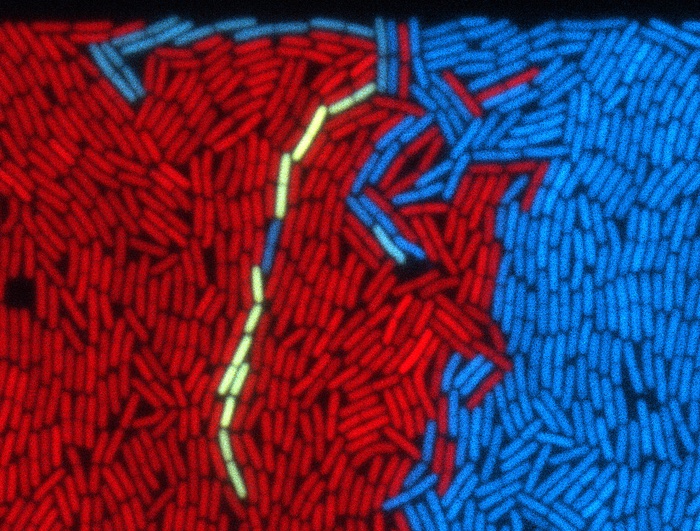

Schwabe & Wolf (2010, p. figure 6)

Sometimes your instrumental actions manifestly run counter to your intentions.

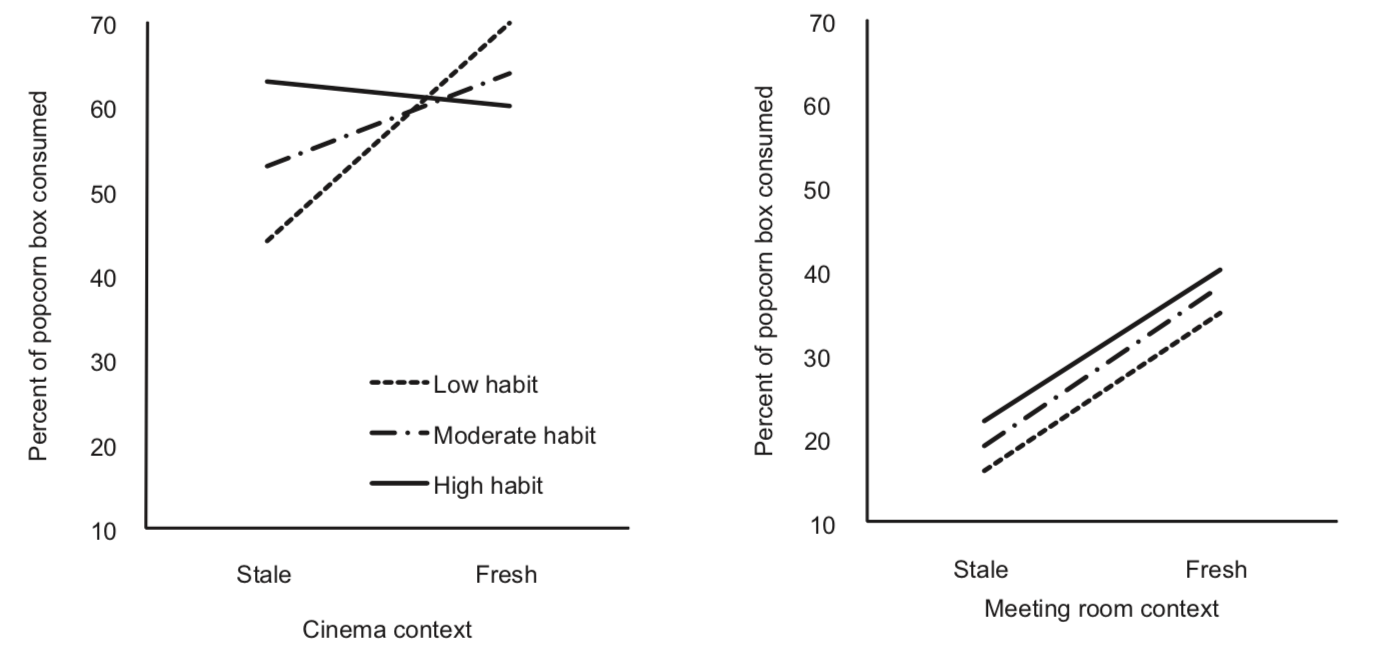

another example—new study (popcorn)

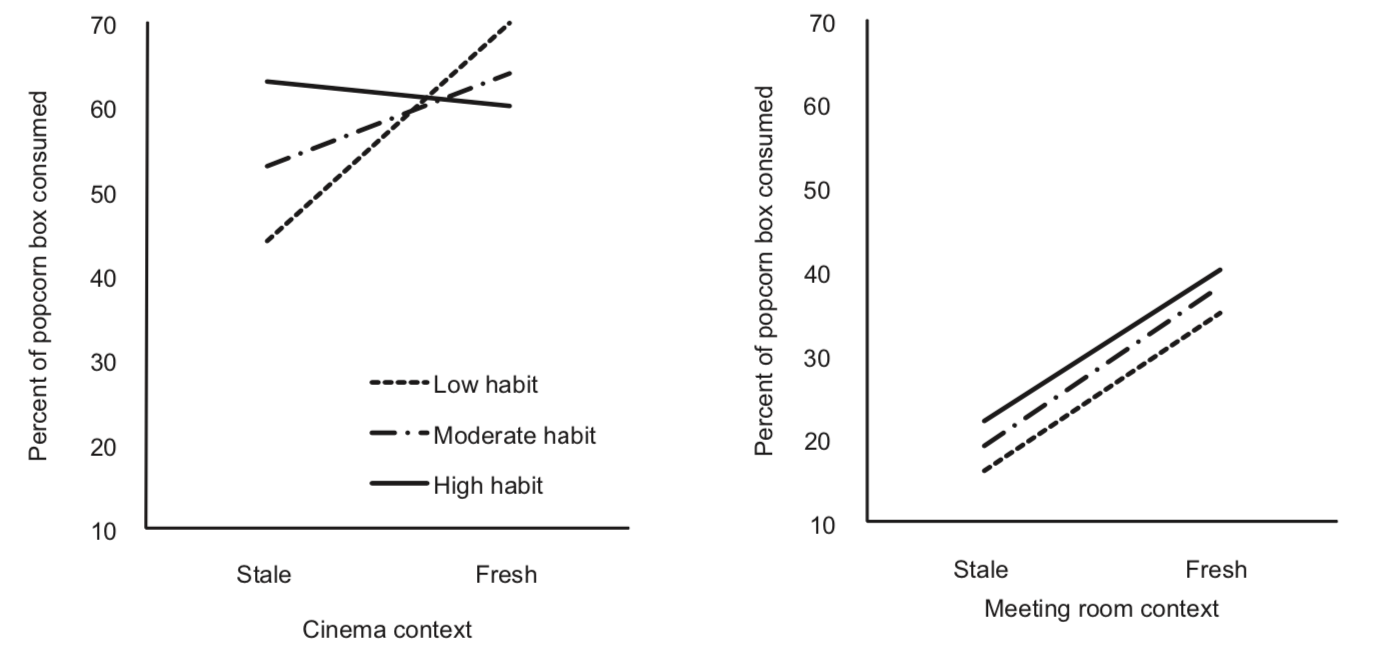

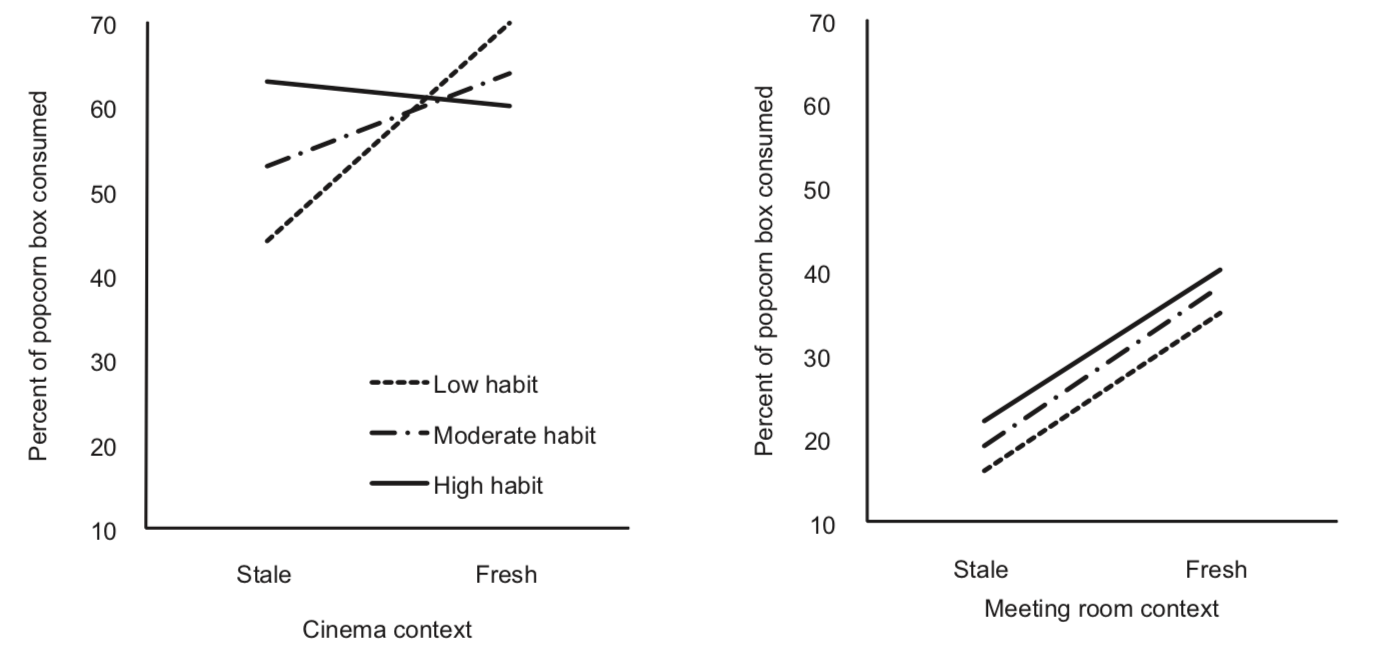

Neal, Wood, Wu, & Kurlander (2011)

Sometimes your instrumental actions manifestly run counter to your intentions.

(this is also a key response to zahidnasser’s question)

What distinguishes your actions from things that merely happen to you? (‘The Problem of Action’)

Standard Solution: actions are those events which stand in an appropriate causal relation to an intention.

‘deviant causal chains’ (Davidson, 1980, pp. 78--9)

Minimally, the action should not manifestly run counter to the intention;and neither should whether the action occurs be independent of what the agent intends.

Objection: some instrumental actions manifestly run counter to the agents’ intentions.

Why is this an objection?

How do we know? From persistence following devaluation!

aside: you can also make this argument using AHS

(Della Sala, Marchetti, & Spinnler, 1991)

response 1

insist there’s an intention

(see zahidnasser’s objection)

Neal et al. (2011)

option (i) - the intention to eat the stale popcorn is more common in ‘high habit’ group ... but only in the cinema

‘strong-habit participants experienced the shift in motivation as a function of the food’s freshness. They rated the fresh popcorn as more likable than the stale, and thus they did not value the popcorn more than those with weak habits. [...]

‘Furthermore, tests of whether the habit effects depended on liking for the popcorn or current hunger revealed that these factors did not moderate the effects of habit strength on eating.’

(Neal et al., 2011, p. 1432)

option (ii) - there are other intentions, perhaps intentions to empty the bag, or intentions to grasp and place

old: stimulus–action + stimulus → action

new: stimulus–action + stimulus → intention → action

option (iii) - intentions are in the background ...

DanielKnoth [2022–23]

Can the standard answer maybe incorporate habitual processes and defend the relationship between intention and action by arguing that when the habit was originally formed, there existed some kind of intention and the more or less automatic process of habitual actions, later on, is still linked to that original intention?

motivational potential (Bratman, 1984)

Desiring to repeat the high from a daily exercise routine,

and using what she knows from studying animal learning,

Ayesha sets a novel and unique alarm sound,

exercises immediately on hearing this alarm,

and treats herself immediately after exercising.

[links to hespercheung’s ‘basketball’ objection]

BUT:

not all stimulus–action links are a consequence of intention!

Neal et al. (2011)

option (i) - the intention to eat the stale popcorn is more common in ‘high habit’ group

option (ii) - there are other intentions, perhaps intentions to empty the bag, or intentions to grasp and place

old: stimulus–action + stimulus → action

new: stimulus–action + stimulus → intention → action

option (iii) - intentions are in the background

What distinguishes your actions from things that merely happen to you? (‘The Problem of Action’)

Standard Solution: actions are those events which stand in an appropriate causal relation to an intention.

‘deviant causal chains’ (Davidson, 1980, pp. 78--9)

Minimally, the action should not manifestly run counter to the intention;and neither should whether the action occurs be independent of what the agent intends.

Objection: some instrumental actions manifestly run counter to the agents’ intentions.

Why is this an objection?

How do we know? From persistence following devaluation!

response 2

deny instrumental actions are all actions

‘Among the things I did were

get up,

wash,

shave,

go downstairs, and

spill my coffee.’

(Davidson, 1971, p. 43)

‘Among the things that happened to me were

being awakened and

stumbling on the edge of the rug.’

(Davidson, 1971, p. 43)

eating popcorn

pressing a button to watch a film clip

What distinguishes your actions from things that merely happen to you? (‘The Problem of Action’)

Standard Solution: actions are those events which stand in an appropriate causal relation to an intention.

‘deviant causal chains’ (Davidson, 1980, pp. 78--9)

Minimally, the action should not manifestly run counter to the intention;and neither should whether the action occurs be independent of what the agent intends.

Objection: some instrumental actions manifestly run counter to the agents’ intentions.

Why is this an objection?

How do we know? From persistence following devaluation!

challenge

Discover why people act,

individually and jointly.